'We are telling a story that is lost': Pinoytown tours uplift long-forgotten history in San Jose

Thriving Filipino community was part of a multiethnic enclave from the 1930s to 1950s

Written by Jamey V. Padojino

Filipino American neighborhoods have made their mark across the U.S., such as Historic Filipinotown in Los Angeles, Little Manilas in Stockton and New York City and Pinoytown in San Jose.

Wait, Pinoytown? Where's that?

It's located in an area widely known today as Japantown, north of the present-day downtown and centered on Sixth Street. But from the 1930s to 1950s, this part of San Jose was an enclave of Chinese, Japanese and Filipinos. "There was a tremendous amount of cooperation and compatibility among us," said Robert Ragsac, 93, who grew up in the neighborhood.

The core of Pinoytown was located on Sixth Street between East Taylor and East Jackson streets in San Jose. It was part of a multiethnic enclave during the 1930s to the 1950s. Courtesy Robert Ragsac/FANHS-SCV.

Chances are you haven't heard of Pinoytown because the name was first coined by Ragsac shortly before he hosted the first tour in March 2019 for a group of De Anza College students. The pilot run was done in partnership with the Filipino American National Historical Society's Santa Clara Valley chapter (FANHS-SCV), which continues to team up with him for the tours.

The first Pinoytown tour in San Jose was hosted for a group from De Anza College in March 2019. Courtesy Ann Reginio/FANHS-SCV.

Ragsac, who's also known as Manong Robert, was born in Pinoytown in 1931 and grew up with his parents and three siblings. The tour is a product of stories he collected in retirement for his childhood friends after they reminisced about the old days.

Attendees are each given a 52-page pamphlet rich with past and present photos of the people and places that shaped the area. While most of the buildings Manong Robert once knew no longer stand, they're captured in the guide provided to visitors, who are asked to imagine the structures. But his rich tales bring the community of yesteryear back to life.

Sixth Street was filled with Chinese and Japanese residents and businesses during the 1920s when the area was known as Chinatown. Filipinos shopped in the area before moving in and setting up their own businesses (such as restaurants, barber shops and pool halls) the following decade. It was a high-traffic hub filled with different voices and food aromas.

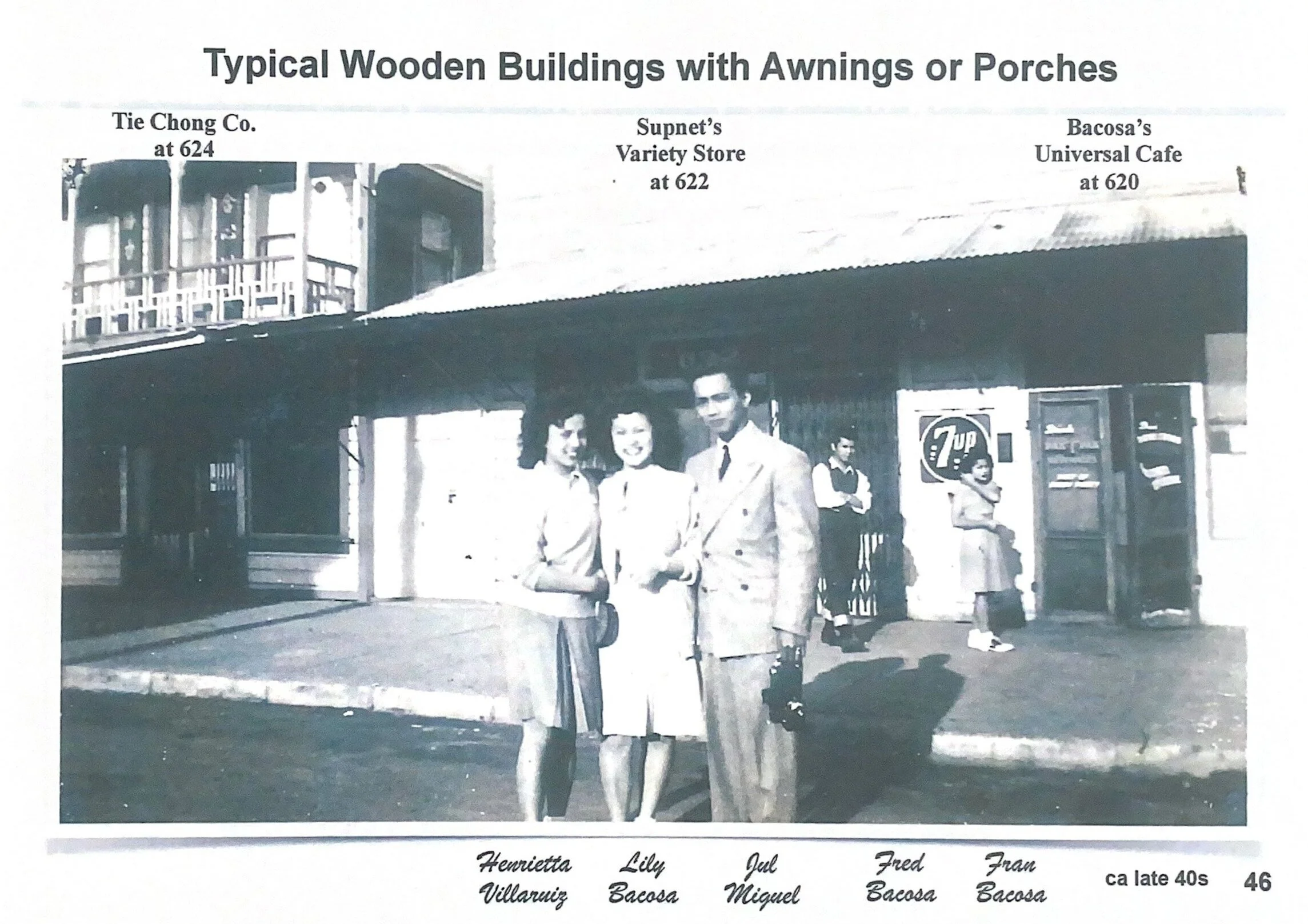

The wooden buildings and wooden boardwalk in this photo were common architecture seen in San Jose's Pinoytown. Courtesy Robert Ragsac/FANHS-SCV.

On a recent tour, Manong Robert painted vivid pictures of his childhood. He was introduced to rice topped with a hot dog and egg cooked over easy at Tom and Mary's Snack Shop (now occupied by Japanese restaurant Gombei). He recalled sneaking into movie nights at the Buddhist Temple with help from his Japanese friends, only to get kicked out for laughing at what he considered overdramatic acting.

He also recounted the day when he saw a Japanese family rush out of their home with clothes and bags. Manong Robert later learned that those neighbors were forced out through Executive Order 9066, which resulted in the mass relocation of Japanese people into internment camps. During this time period, many Japanese trusted Filipinos with their businesses, Ragsac said.

FIlipinos would also have picnics, which in reality were occasions to hold cockfights (known as sabongs in Tagalog). "That's a cultural aspect of the Filipinos that won't die," Ragsac said. Law enforcement were known to raid the gatherings.

Cockfights were just one normal part of the picnic, Manong Robert said. They'd also have barbecue and children would play. Filipinas often sold food at the gatherings, such as lumpia made with wrappers that were cooked like a crepe, said Ann Reginio, FANHS-SCV's chapter administrator.

Filipinos started to move away from the neighborhood in the late 1950s, and the Pinoytown where Ragsac grew up started to fade away. His generation left for various reasons, including marriage, work, college and military service, and younger immigrants weren't interested in running local restaurants or shops. It was the same decade when the area was formally named Japantown.

The Filipino Community Center is the last building from Pinoytown's heyday that still operates today, but there are other physical reminders that honor Filipino history in the neighborhood. Timeline benches are situated around Japantown with QR codes where visitors can learn more about the community, including three capturing Filipino history in the area. A Pinoytown mural by Analyn Bones and Jordan Gabriel outside Kogura Company was unveiled in March 2024, depicting the center and a photo of second-generation Filipino Americans outside a grocery store in the mid-1940s.

From left, artists Gabriel Mendoza and Analyn Bones pose with FANHS-SCV chapter administrator Ann Reginio and Manong Robert Ragsac in front of the Pinoytown mural in San Jose. Courtesy Ann Reginio/FANHS-SCV.

Filipino entrepreneurs have made their way back to the neighborhood, Ann said. One example is Cukui, a clothing store and art gallery that opened its doors soon after its 2008 brand launch.

Just like the camaraderie that was experienced decades ago, the multiethnic enclave continues to uplift each other's stories. Robert has shared stories of Filipinos in the area to the Chinese community alongside historian Connie Young Yu. He has also joined Japantown tours hosted by Curt Fukuda of the local Japanese American Museum, and Curt sometimes joins Pinoytown tours to offer his perspective. "When you do that, you get this overlap and synergy between the two types of tours as well as the ethnic minorities," he said.

"I didn't know that" is a common reaction Manong Robert hears during the tours. People are often surprised by how there was a Filipino Presbyterian Church on Fifth Street, let alone the existence of Pinoytown in the first place. "It almost validates the fact that all the work that we are doing is worthwhile. We are telling a story that is lost."

An estimated 1,000+ people have attended the tours since they launched in October 2020, including families, students and youth groups. Pinoytown has inspired the Bayou Barkada tours in New Orleans, Louisiana, where the first Filipinos settlement was established in the U.S. during the 1700s.

FANHS-SCV chapter administrator Ann Reginio and Manong Robert Ragsac helped establish the Pinoytown tour in San Jose, which launched in October 2020. Courtesy Ann Reginio/FANHS-SCV.

Ragsac and Reginio hope the Pinoytown tour encourages people to record their own family's immigration story.

After the roughly hourlong tour, Ragsac said he anticipates people won't remember 80% of what he said, but he makes two calls to action: interviewing their parents and grandparents, and making a family tree.

"It starts easily at home," Ann said. "You know, having these conversations with people that are still alive is really important. If your Lola and Lola are still there and you don't know your story, it's good for you to explore that."

The tours are open to the public every Sunday in October to celebrate Filipino American History Month and in past years have sold out quickly. They are limited to 15-20 people who need to register beforehand and are free, though donations are encouraged. This year, they will be on Oct. 12, 19 and 26. (The organization is skipping the first Sunday of the month due to the local Rock 'n' Roll Half Marathon.) Outside of October, private, paid tours are arranged in advance by emailing pinoytownsj@gmail.com.

For those who can't make it to San Jose, the tour is also available virtually. The online experience, available at fanhs-scv.org/pinoytownvirtualtour, includes before and after photos of locations captured in the tour.