Azucena | The Filipino-American Poetry Book That Started It All

By Jennifer Redondo

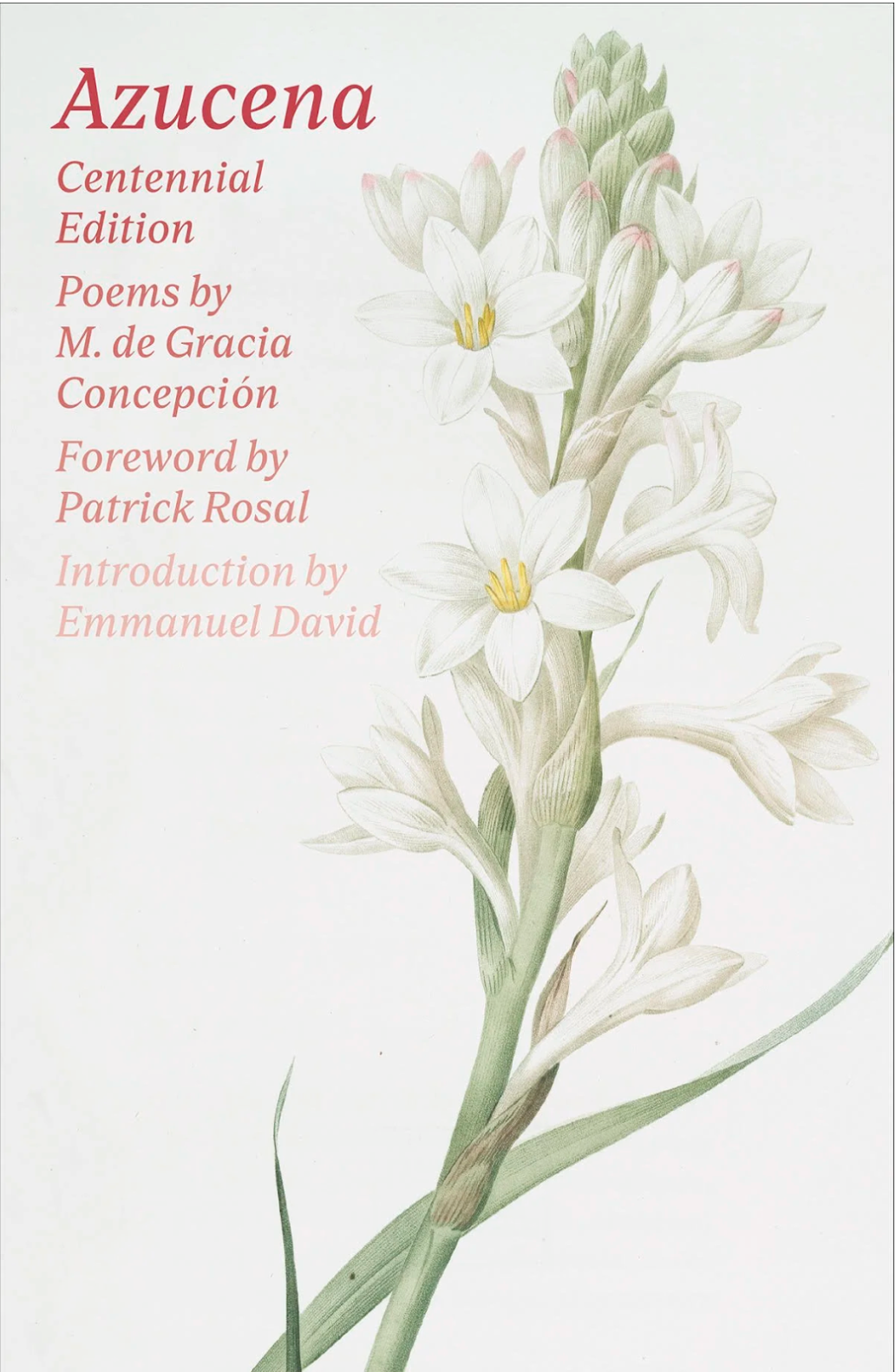

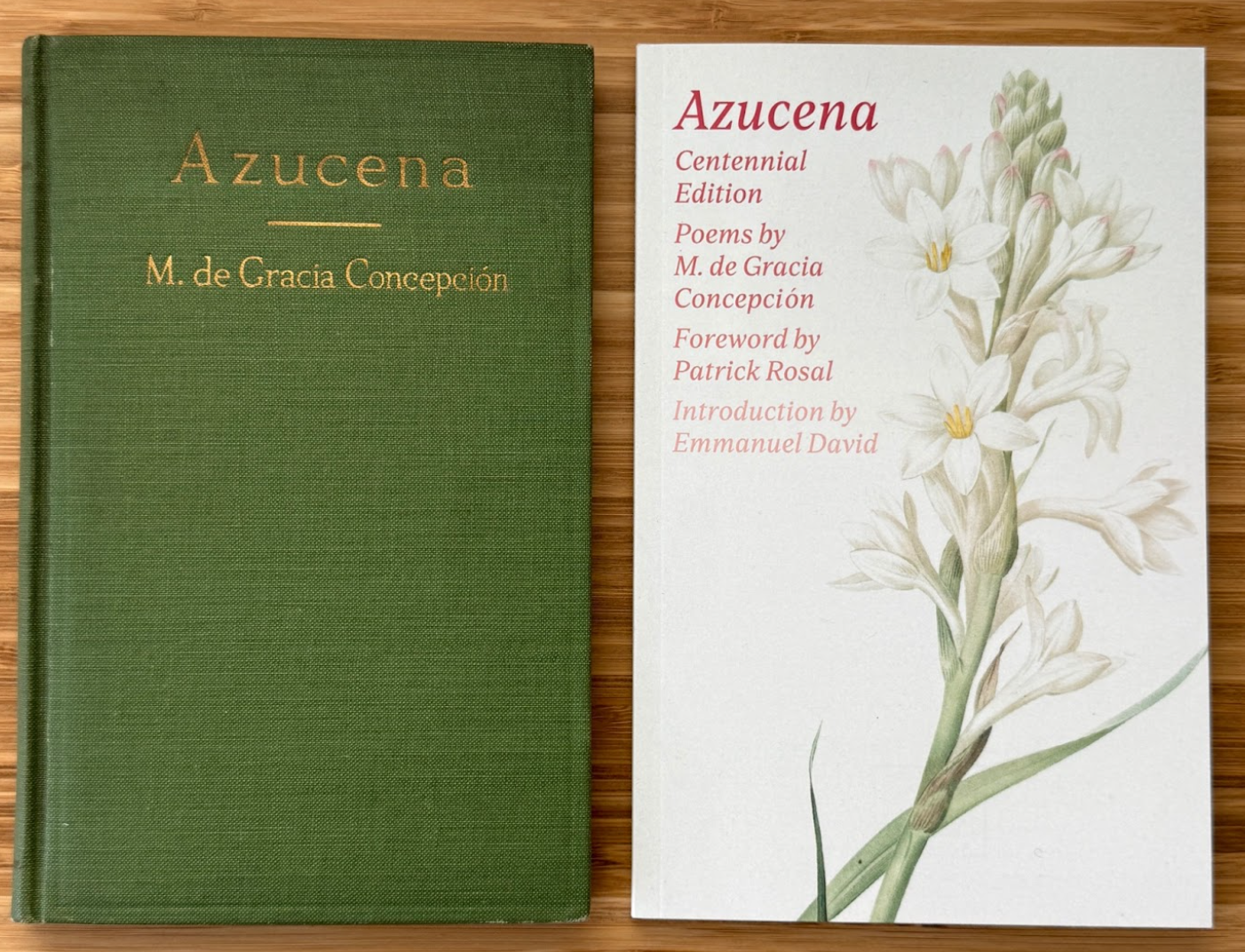

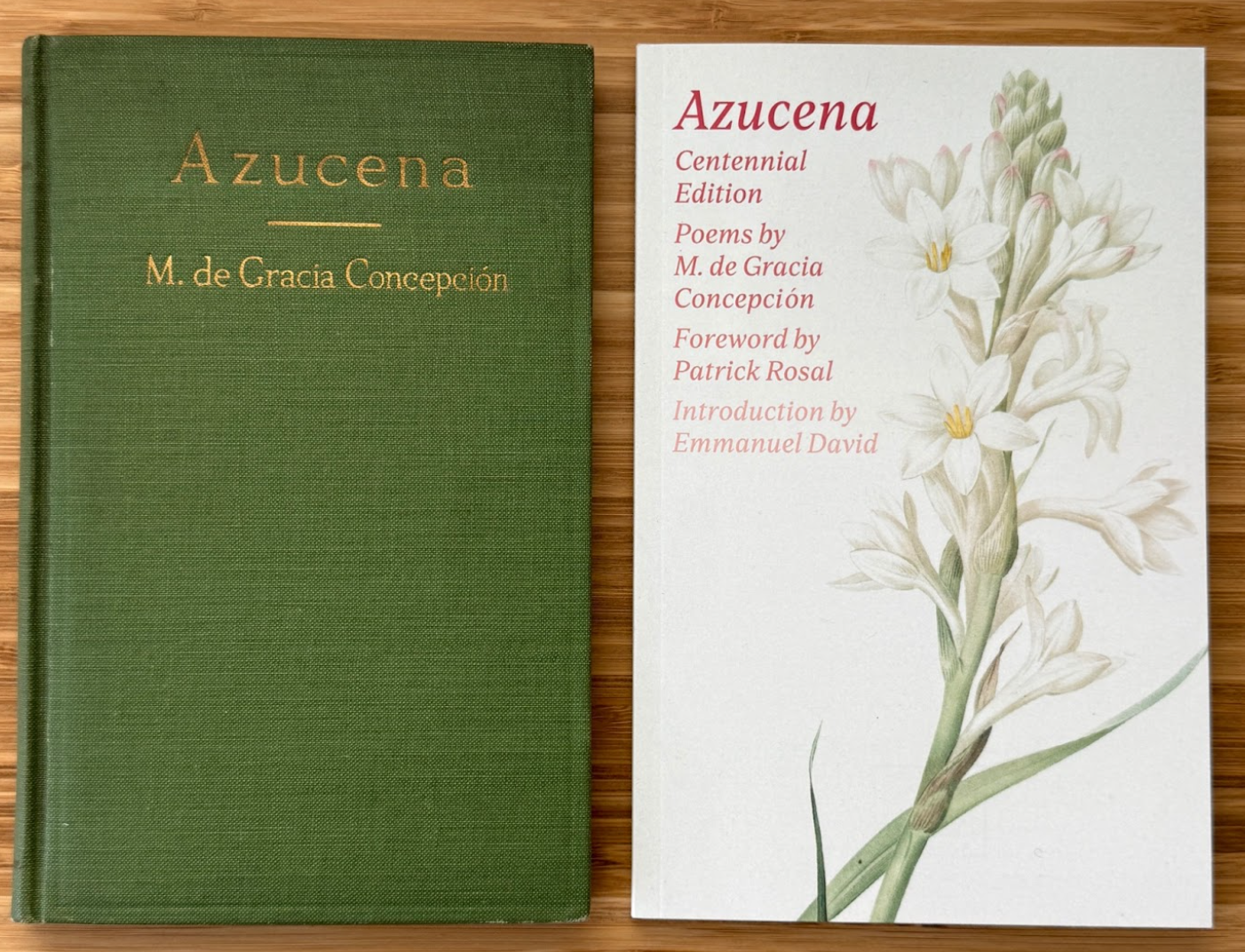

The first poetry book to be published by a Filipino in the United States, Azucena, was written by Marcelo de Gracia Concepcion. Azucena has been republished this month by Persea Books, a century after its initial release (1925-2025). The new edition features a Foreword by Persea's Patrick Rosal and an introduction by Emmanuel David of the University of Colorado Boulder.

To learn more about Azucena, read on as we had the opportunity to learn more from Professor Emmanuel David, a descendant of Concepcion, who shares insights on this project that is deeply personal to him. Thanks to Professor David’s research, readers are able to learn more about a Filipino-American figure who has until now been largely overlooked and forgotten.

1. What is the book’s significance? And why did it take 100 years to reissue?

Emmanuel David: When Azucena was first published in 1925, it offered something seemingly new to North American readers –– the voice of a young, Filipino poet writing in English, or what Concepcion describes in his Foreword as a “borrowed tongue.” Across nineteen poems, Concepcion reflects on feelings of love, loss, and wonder, on experiences of home and displacement, and on an incessant yearning to return to the Philippines. Thinking about broader histories of migration and the Philippine diaspora, his poems capture enduring feelings of melancholy and nostalgia.

Azucena was Concepcion’s first book and it marked just one of many significant moments in his life. As I show in the introduction to the centennial edition, Concepcion earned an important place in Filipino and American literary history, but his biography has remained almost completely unexplored. My archival research for the new edition enabled me to reconstruct Concepcion’s life, detailing not only his contributions to literary history through his writing, but also his contributions –– as an intellectual, activist, newspaper editor, and public critic –– to broader Philippine independence movements. The resulting introduction offers a detailed account of Concepcion’s life both in the Philippines and the United States, and the reissued text makes a literary historical work, long out of print, more widely available to a general public.

As for why it took 100 years to reissue the book, that’s a great question. Perhaps it has to do with literary trends and what types of texts are fashionable at any given moment. But a large part probably has to do with historical bias in the publishing industry and the ease with which immigrants and writers of color are routinely overlooked and forgotten. And finally, I think that elements of chance, fate, and historical circumstances resulted in Concepcion not leaving behind literary papers or an archive of his work. His home in the Paco neighborhood of Manila, for example, was destroyed during World War II, at the peak of his intellectual and literary career, and presumably his papers and other belongings were also lost.

2. What is your relationship with Concepcion?

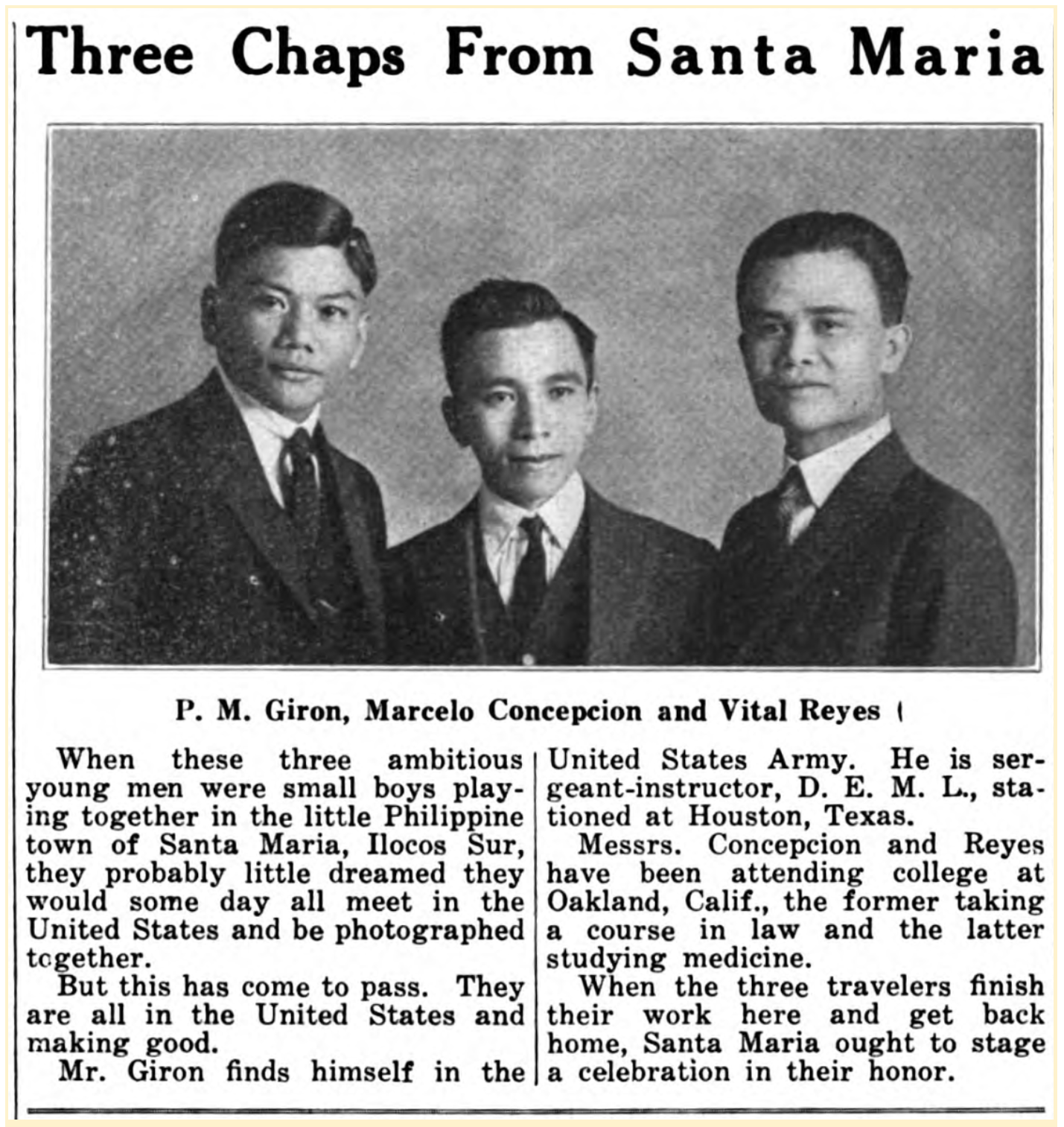

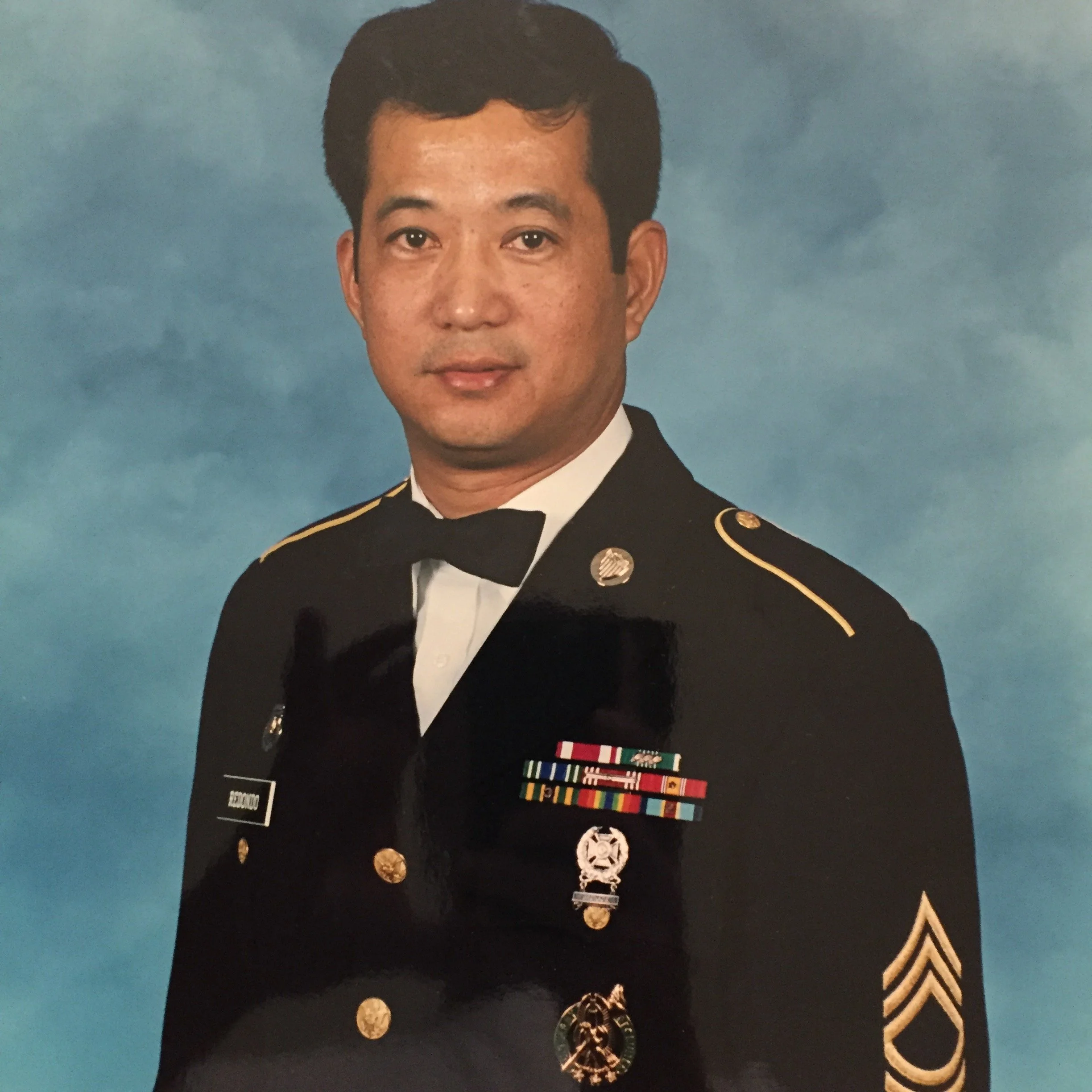

Emmanuel David: Concepcion was my Lola’s uncle. They were both born in Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur, Philippines. When I write about him and his literary influence, I use his last name as a formality. But in other contexts, I refer to him as Lolo Marcelo. He and his American wife had no children, so in some ways I’m one of his closest living descendents and somehow I assumed the responsibility for caring for his memory.

Early on, as I began exploring the idea of reissuing his book of poems, I regularly consulted a hand-drawn family tree that my Lola and her elder sister, Lola Pat, made together. I used this as a primary resource to dig into family history and into Lolo Marcelo’s life.

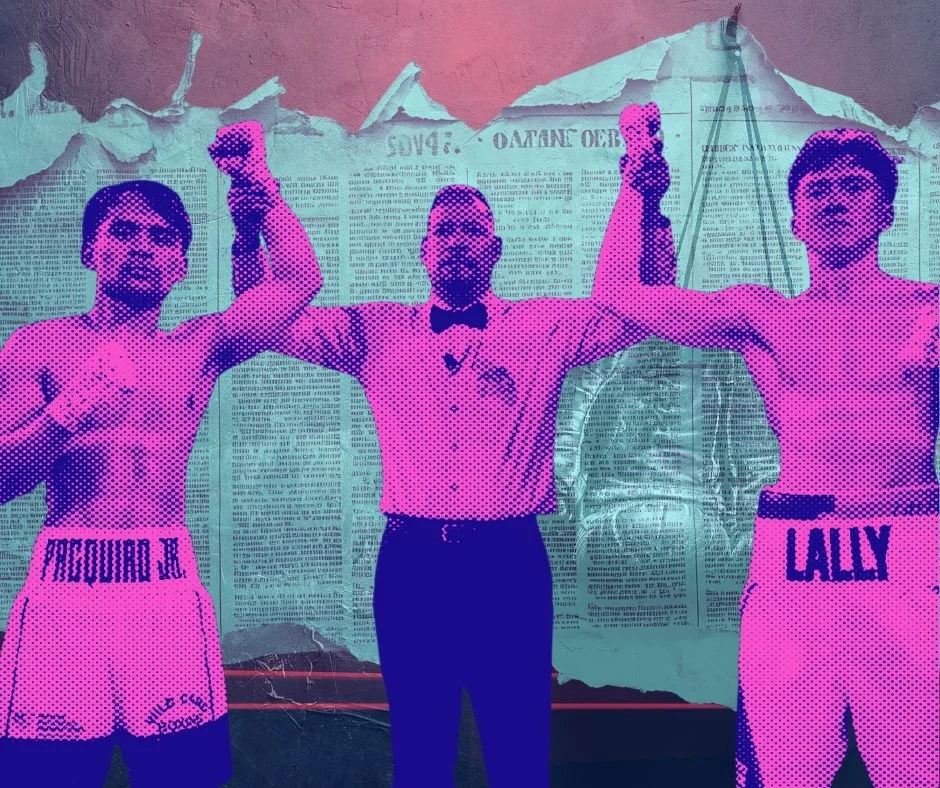

And while my primary focus was on reconstructing the details of Lolo Marcelo’s life, the process also provided me with the opportunity to think about broader connections to Filipino-American history. In many ways, his path to the U.S. was not unlike the migration paths of other Filipinos across history. He served in the U.S. Navy, worked in the canneries, and enrolled in classes in several universities (first at University of Washington and then at the University of California Southern Branch, which turned into UCLA a few years later). And once here in the U.S., like many other Filipinos, he encountered many obstacles, like poverty and racism, and even violent encounters with the police. His story also serves as a window into the broader historical struggles of many Filipinos and Filipino-Americans in the first half of the 20th century.

3. What else would you like to share with potential readers?

Emmanuel David: Sure there are a few things…

First, I really like the book cover, which features botanical images of the azucena flower. The press was really intentional with the design. The font is also a typeface created by Filipino designers.

Second, I am really indebted to Gabriel Fried at Persea Books for believing in this project and for connecting me with Patrick Rosal, who wrote the Foreword to this edition. Rosal is a gifted and prolific writer (check out his book, My American Kundiman, also published by Persea). In his Foreword to this edition of Azucena, he offers some wonderful reflections on the poems and on the historical context in which they were written and for that I am grateful.

And one more interesting thing about him! He played the role of an elderly Tibetan lama in a Hollywood film, Storm Over Tibet, released in 1952. For those interested in seeing him and hearing his voice, you can check out the film here.

4. Where can people purchase this book?

Emmanuel David: The book can be purchased directly from the publisher, Persea Books, or from other online booksellers.

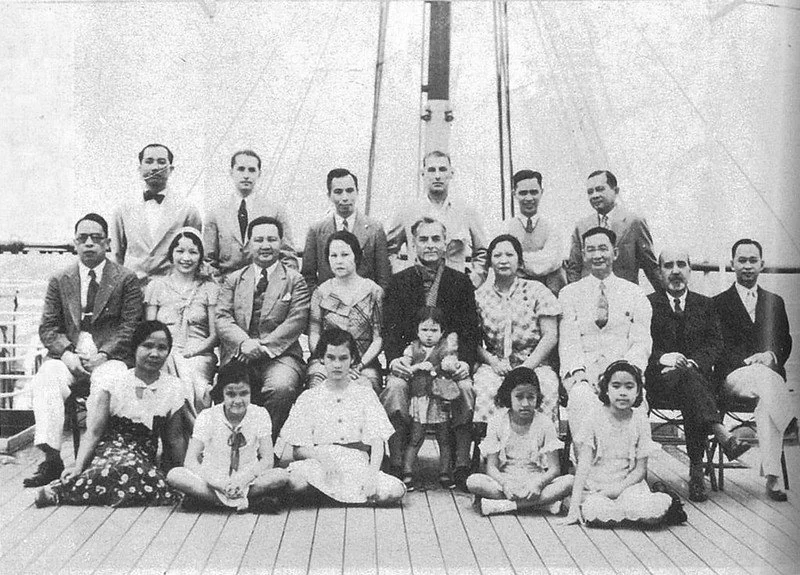

Poet M. de Gracia Concepcion (back row, third from left) on board the S.S. President Hoover en route to Washington D.C. as part of Manuel Quezon’s 1934 independence mission working for the Tydings-Mcduffie Law.

Poet M. de Gracia Concepcion (back row, third from left) on board the S.S. President Hoover en route to Washington D.C. as part of Manuel Quezon’s 1934 independence mission working for the Tydings-Mcduffie Law.

(Photo from Elpidio Quirino: The Judgment of History by Salvador P. Lopez) and posted on the Presidential Museum and Library PH flickr page: https://flic.kr/p/ok93uN

When the Avengers: Doomsday one-year countdown dropped, audiences didn’t just watch. They paused, replayed, shared, and even speculated about hidden messages. A week later, the clip surpassed 14 million views, becoming a viral moment picked up across major media outlets that fueled anticipation for the next chapter of the Marvel Universe.

The countdown video was the result of a collaborative effort led by AGBO and its studio partners. Supporting the marketing team as a contracted editor was Joshua Ortiz (@joshuajortiz), a Filipino American filmmaker whose career has steadily built toward opportunities to contribute to projects of this scale, alongside earlier success with the short films he has written and directed.