We Were Never Half: The Erased Identity of Tsinoys in America

Written by Clifford Temprosa

I didn’t grow up confused about who I was. I grew up in a world that refused to see all of me. Born in the Philippines with a Chinese heritage, raised in America by immigrants who spoke in Tagalog and Hokkien, I learned early that my identity would be misunderstood, questioned, and ignored.

I wasn’t Filipino enough for Filipino Americans. I wasn’t Chinese enough for the Chinese American. And in a country that flattens “Asian” into a single, palatable narrative, I didn’t exist at all. Am I Asian or American? Am I Filipino or Chinese? Common questions I was forced to live with.

But the truth is this: Chinese Filipinos or Tsinoys (Chinoys) have always existed. Before colonizers. Before categories. Before anyone asked us to choose.

Before the Border Was the Bloodline

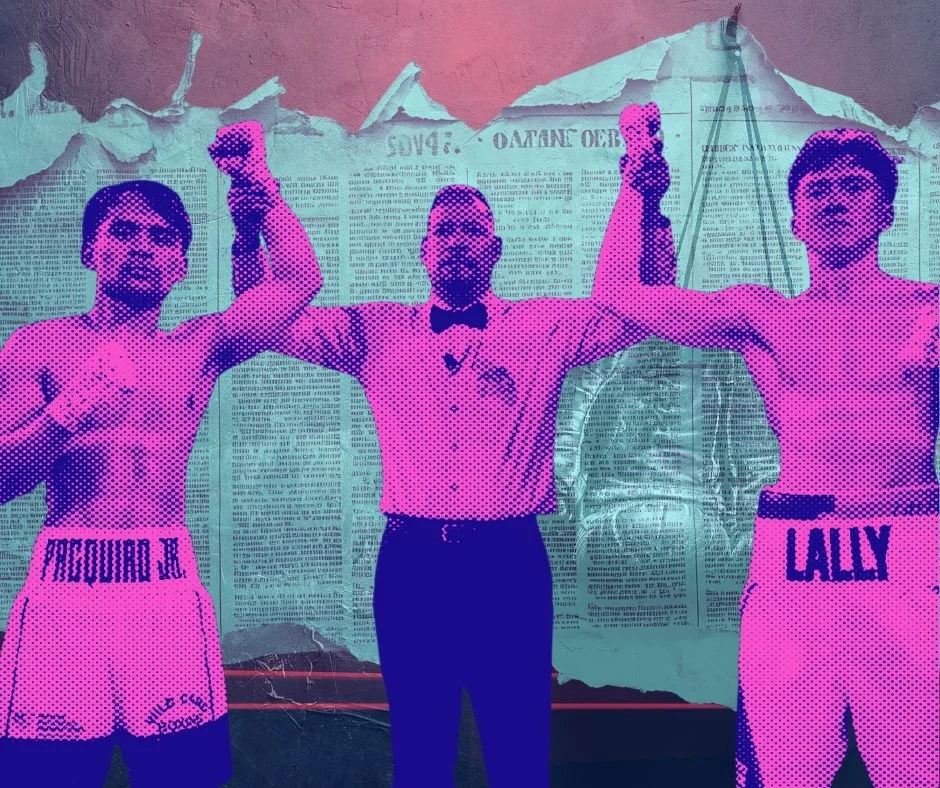

Long before “Filipino” became a national identity, and centuries before the first Spanish galleon docked, Southern Chinese traders, mostly from Xiamen and Jinjiang in Fujian, regularly voyaged to the archipelago. As early as the 10th century, maritime exchanges linked Southern China and precolonial Philippine polities through barter, kinship, and settlement. Historic maps, excavated artifacts, and written records have traced Chinese migration across Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao.

By the 16th century, when Spain colonized the islands, these Chinese migrants (Sangleys derived from the Hokkien word "seng-li," meaning "business" or "trade) were deeply embedded in the local economy and social fabric. Many intermarried with native women and gave rise to a new ethno-cultural community: Lannang, which is a Hokkien-derived term meaning “our people.”

Binondo, Manila, established in 1594, is the oldest Chinatown in the world, built by Spanish decree not as a gift but as a method of containment. What was meant to segregate became a seedbed for economic innovation, interethnic alliance, and resistance.

We were not foreigners. We were family. We were community. We were power.

Erased by Empire, Forgotten by the Diaspora

We know this. Colonization doesn’t just redraw borders, it rewrites identities.

Under Spanish rule, Sangleys were portrayed as “economic threats” and subjected to pogroms and forced conversions.

Under American rule, Sinophobia deepened, and English became a tool of cultural assimilation.

By the 20th century, many Filipino Chinese families erased or downplayed their Chinese roots, a survival mechanism against discrimination, anti-Chinese laws, and local resentment.

In the diaspora, that erasure continues. In the U.S., Filipino identity is often reduced to Spanish and American colonialism. Chinese identity is flattened into Mandarin-speaking East Asian narratives. And Tsinoy identity, a product of precolonial migration, interethnic relations, and multigenerational resistance, is completely absent from the conversation.

When We Were the Other: Racial Tensions Between Filipinos and Lannangs

To understand the full story of being Tsinoy, we have to talk about the parts that hurt.

Because not all erasure came from colonizers. Sometimes, the pain came from people who looked like us. People we called kapitbahay, kababayan, even kaibigan.

For centuries, Chinese Filipinos were treated as “the other.” Not only by Spanish and American powers, but by fellow Filipinos conditioned by colonial caste systems.

During Spanish rule, Lannangs were:

Blamed for controlling trade and wealth

Restricted to ghettos like Binondo

Periodically massacred in the thousands by colonial soldiers with the silent consent of local elites

But post-colonial Philippines didn’t heal the wound, it made it more complex. Throughout the 20th century and even today, Chinese Filipinos were scapegoated for economic inequality, portrayed in the media as smugglers, hoarders, or greedy outsiders.

And yet, Lannangs:

Were denied citizenship until 1975, even if born in the Philippines

Paid special residence taxes for simply being Chinese

Had to purchase Filipino-sounding names to gain access to schools, land, and rights

Were excluded from Filipino identity in national discourse

Even today, the echoes linger:

The word “Intsik” still thrown like a slur

Filipino students taught little to nothing about Binondo’s revolutionary history

Lannangs are still being told, “You’re not really Filipino.”

This is painful. But pain unspoken becomes shame. We must speak truth: Lannang pain is Filipino history too. Healing begins with remembrance. Reconciliation begins with truth-telling.

The History in Our Names: Surnames, Survival, and Storytelling

Our last names are more than family markers. They are maps of migration, erasure, and resistance.

Many of the most common Filipino Chinese surnames, Tan, Sy, Chua, Co, Go, Ong, Chan, Lim, originated from the Hokkien transliterations of Southern Chinese family names.

Because the Spanish colonial government required surnames to be registered, especially for taxation and land ownership, many Chinese Filipinos adapted their names phonetically into Spanish-friendly formats. Others went further: purchasing or creating “Filipino-sounding” surnames to escape discrimination or pass into mestizo privilege.

Some adopted dual identities: one name for church, one for kin. Others were forced into Hispanicized records, their original names lost entirely in colonial clerical systems.

Today, these surnames remain but the stories behind them have faded. Reclaiming their meaning is an act of cultural literacy, ancestral reverence, and political refusal.

Language Loss Is Colonial Violence

Most Filipino Chinese Americans cannot speak Lánnang-uè, the Philippine Hokkien dialect spoken for generations in places like Binondo, Cebu, and Iloilo. The disappearance of Lánnang-uè is not accidental, it’s the result of centuries of cultural erasure, school systems that punished local languages, and internalized shame passed down through generations.

Language is a living archive. And our archive was silenced.

Archiving Ourselves: What So Asian Comics, Lannang Archives, and Now Steaming Are Doing for Our Future

But today, a new generation is refusing to stay invisible.

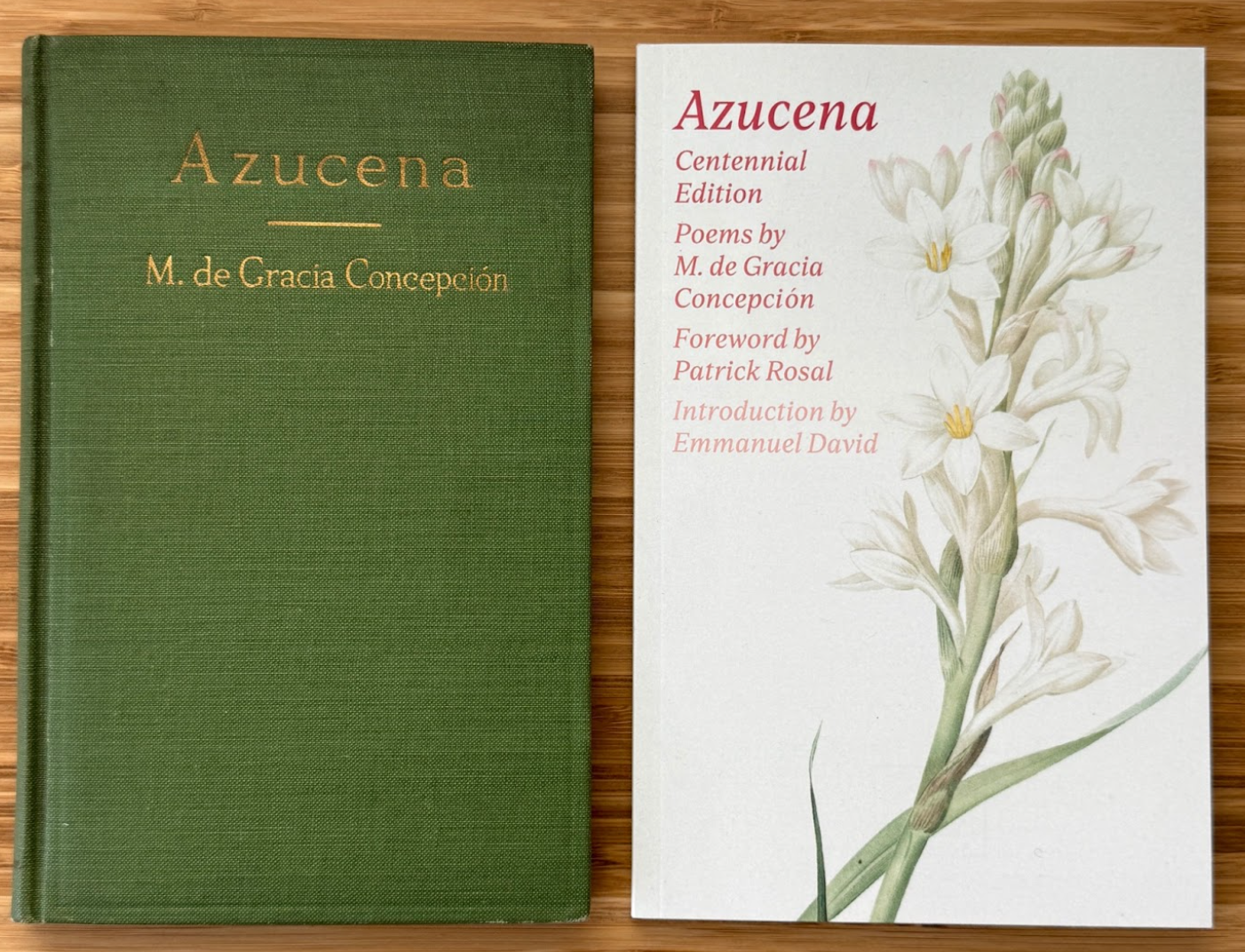

Lannang Archives is more than a digital library, it’s a cultural uprising. The archive documents and protects the histories, languages, rituals, foods, and lifeways of Chinese Filipinos, many of which have never been officially recorded.

They are collecting:

1. Oral histories from elders who remember the rhythms of Lánnang-uè

2. Cultural practices like incense rituals, taboos, and interfaith prayer

3. Research and scholarship that reclaims precolonial Chinese-Filipino exchange

4. Family photos and documents that challenge what “Filipino” has been allowed to mean

At the same time, the Now Steaming podcast gives voice to the stories our parents were too afraid to tell. It’s raw, diasporic, and healing. Every episode explores identity, invisibility, grief, and reclamation from the perspective of Tsinoys navigating culture, memory, and resistance.

Together, these projects are restoring what was almost erased: our ability to name ourselves.

Neither/Nor: Identity and Invisibility

To be Tsinoy is to live in contradiction. In Filipino spaces, we are “tsinito,” exotified but often excluded. In Chinese spaces, we are not Chinese enough. Too Catholic, too brown, too Southeast Asian. In Asian American discourse, we’re invisible altogether. Too complex to fit a checkbox.

We carry the burden of being told we are “mixed.” But those words are symptoms of a system that doesn’t know how to honor complexity, only categorize it.

We are not confused.We are not half. We are a whole people whose history predates the violence that tried to erase us.

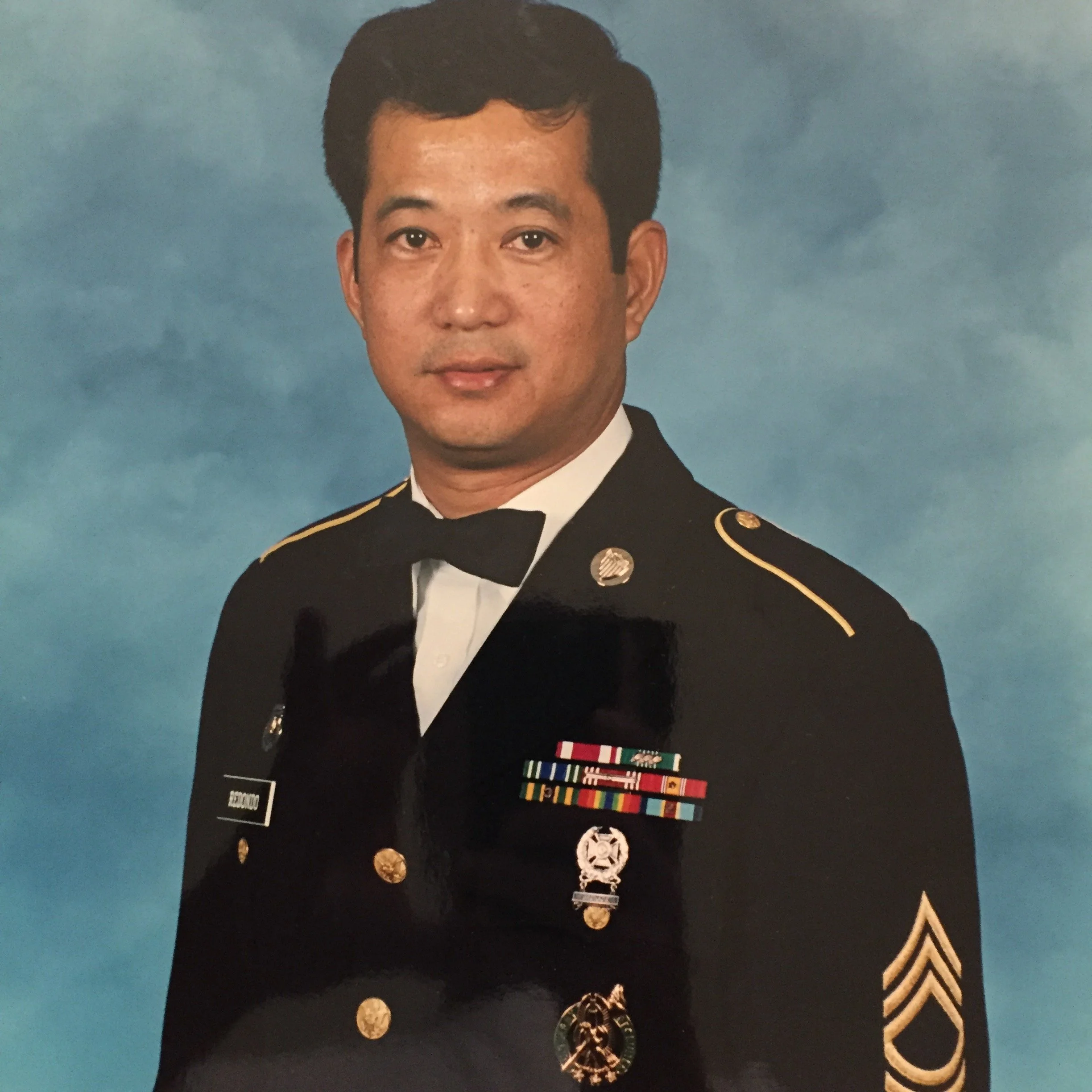

Personal Reflection: Clifford Robin Temprosa Li

For me, being Tsinoy has always felt like a quiet negotiation. At home, we offered food to ancestors with one hand and prayed the Rosary with the other.

My last name, Li, is Chinese. My Chinese name is, 李祈福 which is translated to “praying on good fortune,” My middle names are Tagalog. My life is both.

Growing up, I didn't know how to explain why our family altars had both incense and candles.

Or why we called elders Angkong and Lola in the same sentence. Or why I felt too Chinese for Filipinos, too Filipino for Chinese Americans, and too layered for a country that wants simple stories.

But as I built my life in public service, nonprofit leadership, and advocacy, I realized: my in-betweenness is my gift. I can navigate multiple cultural worlds because my ancestors did it first. I can build bridges because I come from a lineage of bridge-builders.

And now, I no longer shrink my complexity to fit in. I use it to carve space, for myself, for others, for the memory of our people.

Personal Reflection: Stacey Diane Arañez Litam, PhD

Growing up, tsinay was a dance in divergence. The qualities that made me different were endlessly pointed out. I had darker skin than my Chinese cousins, smoother hair than my Filipino cousins, and cheeks that always felt too round for my face. I ate lechon while wearing red on birthdays, burned incense next to Santo Niño, and honored kong kong, amaa, lolo, and lola. I didn’t see my identity represented anywhere and I was constantly pivoting in between cultures, attempting to justify my identity as “enough.”

As an adult who is passionate about leaving legacies of hope and well-being through research, storytelling, and education, I leverage my Lannang identity as an invaluable source of strength. It feels impossible to know where one part of my identity begins and another one ends, because being Tsinay is a core part of my identity. Our stories encompass the ancestral wisdom, generational strengths, and histories of our communities. Our bones are fortified by the struggle, resilience, and resistance of our ancestors. - To be Tsinay is to embody an ancestral blessing.

Navigating In-Between: A Future for Lannangs and Filipinos in America

To every Lannang trying to find language for your identity in a country that flattens you, you don’t have to choose between Filipino and Chinese. You don’t have to apologize for being complex, multilingual, or culturally layered. You are the embodiment of maritime migration, kinship across kingdoms, and survival through centuries of forced forgetting.

In America, you may feel pressure to “simplify” who you are. But the truth is: being Lannang is a complete identity, not a fraction of two cultures.

You can hold both incense and rosary. You can pray in Hokkien, think in Tagalog, and speak in English. You can say your name without needing to explain it.

For Filipino Americans: Chinese Filipino history is your history, too. It’s the story of Binondo, of labor and revolution, of cross-cultural family-making long before colonizers drew lines. Learning about Lannang heritage is not about inclusion, it’s about restoring what was erased from the Filipino story.

So learn the names: Sy, Tan, Chua, Co, Ong. Learn the legacies: The oldest Chinatown. The anti-Chinese massacres. The mixed-race children baptized under Spanish pressure. Learn the power: That even in marginalization, we built cities, shaped economies, and carried culture across oceans.

Solidarity starts with history. And the future of Filipino America includes all of us, or it is not a future at all.

Fall is that sweet time of the year when going to a cozy cafe hits the spot. Visiting a place that celebrates Filipino culture makes the stop an experience in itself. While not exhaustive and in no particular order, here's a list of 10 Filipino cafes for an autumnal escape.

Read More